New Research Exposes the Salt Myth: What Science Really Says About Salt and Health - PART 3

If the historical evidence for salt reduction was flimsy, what does more recent, comprehensive research tell us? In the past 10–15 years, a wave of studies, from large epidemiological analyses to systematic reviews, has challenged the simplistic “salt = hypertension = heart disease” narrative. These findings reveal a far more complex picture in which moderate salt intake is often harmless (or even beneficial), and both extremely high and extremely low intakes can be problematic. Let’s break down some key insights from modern research:

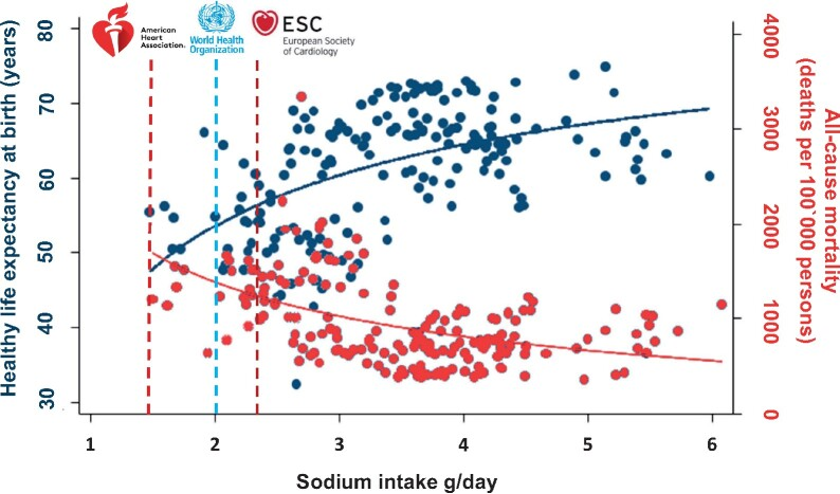

Figure: Relationship between average sodium intake and health outcomes worldwide.

In a study of 181 countries, researchers found that higher sodium intake correlates with longer healthy life expectancy (blue points/line) and lower all-cause mortality (red points/line), after adjusting for factors like GDP and BMI[1][2].

The vertical dashed lines (~2 grams of sodium per day) indicate the strict sodium limits recommended by groups like the AHA and WHO notably, these low intakes are associated with shorter life expectancy and higher death rates in this analysis. Intakes in the range of ~3–5 g/day sodium (far to the right of the guideline limits) were linked to the best outcomes.

This observational data suggests that population-wide low-salt advice may be misplaced, though it doesn’t prove causation.

More Salt, Longer Life? An eye-opening 2020 analysis published in the European Heart Journal examined sodium intake versus life span across 181 countries. The findings directly contradict the idea that more salt shortens life. In fact, countries that ate more salt tended to have longer life expectancies, even when controlling for economic factors and BMI[1][2].

Specifically, every extra gram of daily sodium was associated with about 2.6 more years of healthy life expectancy at birth on average[2].

Conversely, higher salt was associated with lower all-cause mortality rates worldwide[3][4].

Even when the researchers focused only on 46 high-income countries (to reduce confounding from poverty and malnutrition in some low-salt countries), the positive correlation between salt intake and longevity held strong[5].

Their conclusion: these data “argue against dietary sodium intake being a culprit of curtailing life span or a risk factor for premature death.”[6]

In plain English, the countries where people eat a lot of salt are not dropping dead sooner, if anything, they seem to live longer. (Examples: Japan, known for its traditionally high-salt cuisine, also boasts one of the world’s highest life expectancies; other high-salt-intake nations like Spain and France have lower heart disease rates than many low-salt-adherent countries[7], likely due to overall diet/lifestyle patterns.)

Of course, this kind of epidemiological study can’t prove that salt itself is the secret to longevity, but it certainly undermines the notion that salt is a deadly poison to be universally avoided.

If the mainstream dogma were true, we’d expect high-salt countries to have markedly shorter lifespans, and that’s just not the case[8][9].

The J-Shaped Curve: Too Little Salt is as Bad as Too Much. A consistent theme in recent research is that the relationship between sodium and health follows a U-shaped or J-shaped curve[10].

This means both extremes, very high and very low salt intake, are associated with worse outcomes, whereas the middle range is the “sweet spot.” For example, large cohort studies (including the PURE study and others) have found that people excreting around 3 to 5grams of sodium per day (which corresponds to roughly 7.5–12.5 g of salt, since salt is ~40% sodium) tend to have the lowest risk of cardiovascular events and mortality[11].

Risks start to creep up at intakes above about 5–6 g sodium (that’s >12–15 g salt), but they also increase at intakes below ~2.5 g sodium[12].

In fact, consuming too little salt appears to activate various physiological stress pathways. When sodium intake is very low, the body responds by ramping up the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) – a hormonal system that increases blood pressure and fluid retention to conserve sodium[13].

Paradoxically, this means that cutting salt too much can trigger changes that raise heart risk factors even as BP falls. For instance, one meta-analysis noted that low-salt diets caused significant increases in renin, aldosterone, noradrenaline (norepinephrine), cholesterol, and triglycerides compared to higher salt diets[14].

Blood pressure might drop slightly with severe sodium restriction, but adverse changes like higher LDL (bad cholesterol) and stress hormones could offset any benefit [13][15].

No Clear Benefit on “Hard” Outcomes: As mentioned, multiple reviews have failed to find solid evidence that lowering salt prevents heart attacks or extends life in the general population[17][18].

A Cochrane review initially claimed modest mortality benefits to salt reduction in some groups, but after corrections were made, those benefits largely disappeared (the effect of low salt was revised to “non-significant”)[19].

In patients with normal blood pressure, cutting salt has no statistically significant benefit on cardiovascular outcomes according to systematic reviews[20].

Even in people with hypertension, the expected outcome improvements from severe sodium restriction have been surprisingly elusive or small. For example, one large analysis found that reducing sodium did lower stroke and heart attack rates in hypertensive patients, but only with a very minor effect and primarily in those who also had inadequate potassium intake (suggesting the benefit might come from the accompanying dietary changes, not sodium reduction alone)[21][22].

On the flip side, some clinical trials in specific groups have shown worse outcomes with strict sodium limits. A 2011 meta-analysis in Heart Failure patients found that those who restricted sodium had a 160% higher risk of death than heart failure patients who consumed normal or higher sodium diets[23].

In other words, for certain medical conditions, cutting salt can be counterproductive, a stark warning that more salt is not always the biggest problem.

Blood Pressure vs. Health – The Disconnect: How can it be that salt, which does have an effect on blood pressure, doesn’t show a clear benefit on actual health outcomes when reduced?

This puzzle highlights a critical point: blood pressure is a risk factor, not an end in itself[24].

Yes, high blood pressure is associated with increased risk of heart disease and stroke, but focusing narrowly on one risk factor can be misleading.

Salt intake’s effect on blood pressure is relatively modest in most individuals (except those with salt-sensitive hypertension). As one expert quipped, if you take someone with a typical BP of 120/80 and put them on a strict low-salt diet, they might go to 119/79[25], hardly a life-changing drop.

Moreover, reducing BP by cutting salt doesn’t guarantee better health if other mechanisms kick in. We’ve seen that low salt can trigger hormonal changes (RAAS activation, increased sympathetic tone) and metabolic changes (insulin resistance, dyslipidemia) that might negate the benefit of a few points’ lower blood pressure[13][26].

Indeed, research has documented that insulin resistance can increase on a low-sodium diet, likely due to elevated stress hormones and possibly because very low sodium may worsen metabolic stress[27].

This is one reason why simply chasing a BP number by slashing salt is an oversimplification.

Functional medicine looks at the body holistically: if a dietary change lowers one risk factor but raises another, is it truly beneficial? The evidence suggests that for many people, the small BP reduction from heavy salt restriction provides no net health gain, and could even be detrimental if it causes other imbalances.

The Salt Sensitivity Factor: It’s important to acknowledge salt-sensitive hypertension is real, some individuals (often older adults, those of African or East Asian ancestry, or people with kidney issues) do experience significant blood pressure reductions when they cut salt.

For these folks, excessive salt can be harmful, and weight loss, improved insulin sensitivity, and adequate potassium can help reduce that salt-sensitivity[28].

However, trying to enforce ultra-low sodium on the entire population is neither necessary nor effective. Genetics and overall diet modulate how our bodies handle salt[28].

If you are salt-sensitive, a functional approach would be to improve your metabolic health (through diet and lifestyle) which can change your salt sensitivity, rather than simply banning salt forever[29].

For the vast majority (the “salt-resistant” individuals), eating a moderate amount of salt has minimal impact on BP or health as long as the diet is balanced. As Dr. Lawrence Appel (who chaired the 2010 US Dietary Guidelines committee) admitted, “It’s tough to nail these associations” when it comes to salt and outcomes, precisely because of individual variability[30].

Your friend might eat potato chips and never see a BP spike, while you bloat up after a soy-sauce laden takeout meal, we’re not all the same.

Thus, personalisation is key: current science supports a nuanced message that moderate salt is fine (even beneficial) for most, whereas certain sensitive groups should moderate intake, ideally in conjunction with addressing why they are sensitive (such as improving their potassium intake, magnesium status, body weight, and sugar intake, which we’ll cover soon).

In sum, modern research is shaking the foundation of the salt = bad paradigm. We find that eating a moderate amount of salt is generally safe for healthy people, and there’s a broad range (roughly 2.3 to 5 grams of sodium per day, equivalent to 1–2 teaspoons of salt) that is not associated with increased cardiovascular risk[11].

Only at very high levels (likely >5 g sodium per day, which few people reach consistently) does risk climb, and similarly, intakes that are too low (<2–2.5 g sodium) are linked to problems[11].

Unfortunately, this “moderation is fine” message has not yet supplanted the older “lower is always better” mantra in public health circles. Why? Let’s look at that next.